Yesterday I had the privilege of giving some lectures at the London Centre for Spirituality as part of my current 'Pursuit of the Soul'. We had some lively conversations so I didn't cover everything I had prepared. Here is a part I omitted, for those who were there yesterday, and to give a flavour to those who weren't there. It seems I am on the trail of Merton right now! I have some more news about our Catholic Dialogue Conference in June which I will be posting shortly... watch this space!

Yesterday I had the privilege of giving some lectures at the London Centre for Spirituality as part of my current 'Pursuit of the Soul'. We had some lively conversations so I didn't cover everything I had prepared. Here is a part I omitted, for those who were there yesterday, and to give a flavour to those who weren't there. It seems I am on the trail of Merton right now! I have some more news about our Catholic Dialogue Conference in June which I will be posting shortly... watch this space!Best wishes

Peter

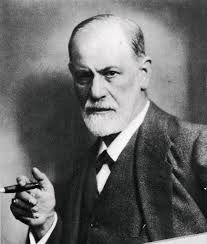

Freud, the ‘godless

Jew’, may not have been a militant atheist but the mental map he developed is

essentially a godless one. There is no room for the transcendent in Freud’s

schema and it would prove to him and his followers at best a distraction and at

worst a hindrance to good mental functioning. It is perfectly possible to

follow all the ideas of the object relations school without any place for the

transcendent. Freud himself vacillated during his life from being actively

opposed to the transcendent to seeing it as an irrelevance. The key aspect for

good mental functioning was appropriate ego strength and an ability to be open

to the ‘unknown thing’ with a listening ear to its demands.[1]

When we survey the current practice of

spiritual direction in the West, and indeed much writing on Christian

spirituality, one of the most surprising things is the extent to which so many

Christian writers take the paraphernalia of Freudian analysis and apply it

unthinkingly to the Christian position. As Freudian language became widespread

in the mid-twentieth century so Christian writers, at first sceptical, adapted

it to their musings. A good example of this is the twentieth century Trappist

monk and social activist, Thomas Merton (1915 – 1968).

As a young man wanting to reject Christian

values Merton had turned towards psychoanalysis. At this point he saw analysis

as offering an opportunity to ‘indulge the appetites’:

I, whose chief trouble was that my soul and

all its faculties were going to seed because there was nothing to control my

appetites – and they were pouring themselves out in an incoherent riot of

undirected passion - came to the

conclusion that the cause of all my unhappiness was sex-repression! ( Merton

1948:124)

This quote comes from the Seven Storey Mountain, his

best-selling autobiography published in 1948 and charting his journey from

pre-war hipster to post-war monk. In it he is censorious about

psychological analysis and suggests ‘if I ever had gone crazy, I think

psychoanalysis would have been the one thing chiefly responsible for it.’ This

sense of mistrust towards analysis is typical of the time.

However, as he continued to live at the

Trappist monastery of Gethsemani in Kentucky, coming into increasing conflict

with his abbot, Dom James Fox, and wondering if the Cistercian vocation was

right for him afterall, he became increasingly interested in psychoanalysis.

Prompted by meetings with the psychiatrist Gregory Zilboorg he began to take

this element of the personality more seriously so that by the time he was

addressing his conferences to novices in the abbey in the 1960s he begins to

use a lot of psychological, and Freudian terms. He also became increasingly

interested in types of what we would today call ‘transpersonal psychology’ that

took the spiritual life seriously and sought to integrate it into psychological

development to which we shall return at the end of this chapter.

Of all Christian writers in the latter half

of the twentieth century interested in Christian spiritual direction, Merton is

something of a pioneer. Although flawed, his last books reveal an attempt to

integrate the findings of psychological analysis with spiritual insight. In Contemplative

Prayer[2], for

example, the integration of the two is almost seamless and he writes with

mastery of the spiritual life using tropes from the early Desert fathers, John

of the Cross and metaphors from Freud such as ‘the ego’ and ‘the unconscious’

with ease:

The ‘flame’ of which St John of the Cross is

speaking is a true awareness that one has died and risen in Christ. It is an

experience of mystical renewal, an inner

transformation brought about entirely by the power of God’s merciful

love, implying the ‘death’ of the self-centred and self-sufficient ego and the

appearance of a new and liberated self who lives and acts ‘in the Spirit’.

(1973:110)

In this respect these later writings come close to the ideal of

psychological language as ‘mystical discourse’ which I am presenting here. The

only problem with such appropriation is that it can tend to blur the original

significance of the terms for a writer such as Freud: a significance we have

described in this chapter. For Merton, the psychological tropes of Freud

offered a means of examining his life as a ‘reintegration of the self in

Christ’ through the marriage of different poles of the self. Merton, living

from the unconscious as a young man embraces the hard ethical demands of the

Christian life when he enters Gethsemani. Only with age and experience does he

realise that the hard edges of ego-control have to be surrendered to allow a

softer entrance of the spirit into all aspects of the self, bringing about what

Blake, his great inspiration, calls the ‘marriage of heaven and earth’. This is

far from the inner psychic conflict that Freud imagined and points more to

influence of his one time collaborator and student, Carl Gustav Jung.

No comments:

Post a Comment